I hated the dismal little 'slavey' who, twice a week, on an average, would bring him up to me. If she smiled as she handed me the packet, I fancied she was jeering at me. If she looked sad, as she more often did, poor little over-worked slut, I thought she was pitying me. I shunned the postman if I saw him in the street, sure that he guessed my shame.

'Did anyone ever read you out of all those I sent you to?' I ask him.

'Do editors read manuscript by unknown authors?' he asks me in return.

'I fear not more than they can help,' I confess; 'they would have little else to do.'

'Oh,' he remarks demurely, 'I thought I had read that they did.'

'Very likely,' I reply; 'I have also read that theatrical managers read all the plays sent to them, eager to discover new talent. One obtains much curious information by reading.'

'But somebody did read me eventually,' he reminds me; 'and liked me. Give credit where credit is due.'

'Ah, yes,' I admit; 'my good friend Aylmer Gowing—the "Walter Gordon" of the old Haymarket in Buckstone's time, "Gentleman Gordon" as Charles Matthews nicknamed him—kindliest and most genial of men. Shall I ever forget the brief note that came to me four days after I had posted you to "The Editor—Play":—"Dear Sir, I like your articles very much. Can you call on me to-morrow morning before twelve?—Yours truly, W. Aylmer Gowing."'

So success had come at last—not the glorious goddess I had pictured, but a quiet, pleasant-faced lady. I had imagined the editor of Cornhill, or the Nineteenth Century, or The Illustrated London News writing me that my manuscript was the most brilliant, witty, and powerful story he had ever read, and enclosing me a cheque for two hundred guineas. The Play was an almost unknown little penny weekly, 'run' by Mr. Gowing—who, though retired, could not bear to be altogether unconnected with his beloved stage—at a no inconsiderable yearly loss. It could give me little fame and less wealth. But a crust is a feast to a man who has grown weary of dreaming dinners, and as I sat with that letter in my hand a mist rose before my eyes, and I—acted in a way that would read foolish if written down.

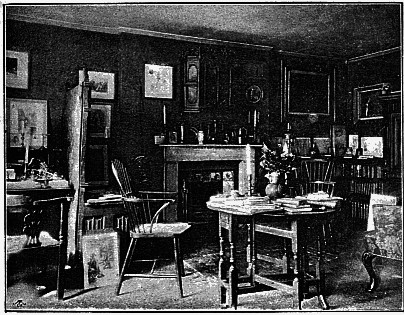

The next morning, at eleven, I stood beneath the porch of 37 Victoria Road, Kensington, wishing I did not feel so hot and nervous, and that I had not pulled the bell-rope quite so vigorously. But when Mr. Gowing, in smoking-coat and slippers, came forward and shook me by the hand, my shyness left me. In his study, lined with theatrical books, we sat and talked. Mr. Gowing's voice seemed the sweetest I had ever listened to, for, with unprofessional frankness, it sang the praises of my work. He, in his young acting days, had been through the provincial mill, and found my pictures true, and many of my pages seemed to him, so he said, 'as good as Punch.' (He meant it complimentary.) He explained to me the position of his paper, and I agreed (only too gladly) to give him the use of the book for nothing. As I was leaving, however, he called me back and slipped a five-pound note into my hand—a different price from what friend A. P. Watt charms out of proprietors' pockets for me nowadays, yet never since have I felt as rich as on that foggy November morning when I walked across Kensington Gardens with that 'bit of flimsy' held tight in my left hand. I could not bear the idea of spending it on mere mundane things. Now and then, during the long days of apprenticeship, I drew it from its hiding-place and looked at it, sorely tempted. But it always went back, and later, when the luck began to turn, I purchased with it, at a second-hand shop in Goodge Street, an old Dutch bureau that I had long had my eye upon. It is an inconvenient piece of furniture. One cannot stretch one's legs as one sits writing at it, and if one rises suddenly it knocks bad language into one's knees and out of one's mouth. But one must pay for sentiment, as for other things.

In The Play the papers gained a fair amount of notice, and won for me some kindly words; notably, I remember, from John Clayton and Palgrave Simpson. I thought that in the glory of print they would readily find a publisher, but I was mistaken. The same weary work lay before me, only now I had more heart in me, and, having wrestled once with Fate and prevailed, stood less in fear of her.

Sometimes with a letter of introduction, sometimes without, sometimes with a bold face, sometimes with a timid step, I visited nearly every publisher in London. A few received me kindly, others curtly, many not at all. From most of them I gathered that the making of books was a pernicious and unprofitable occupation. Some thought the work would prove highly successful if I paid the expense of publication, but were less impressed with its merits on my explaining to them my financial position. All kept me waiting long before seeing me, but made haste to say 'Good day' to me.

I suppose all young authors have had to go through the same course. I sat one evening, a few months ago, with a literary friend of mine. The talk turned upon early struggles, and, with a laugh, he said: 'Do you know one of the foolish things I love to do? I like to go with a paper parcel under my arm into some big publishing house, and to ask, in a low, nervous voice, if Mr. So-and-so is disengaged. The clerk, with a contemptuous glance towards me, says that he is not sure, and asks if I have an appointment. "No," I reply; "not—not exactly, but I think he will see me. It's a matter of importance. I shall not detain him a minute."

'The clerk goes on with his writing, and I stand waiting. At the end of about five minutes, he, without looking up, says curtly, "What name?" and I hand him my card.

'Up to that point, I have imagined myself a young man again, but there the fancy is dispelled. The man glances at the card, and then takes a sharp look at me. "I beg your pardon, sir," he says, "will you take a seat in here for a moment?" In a few seconds he flies back again with "Will you kindly step this way, sir?" As I follow him upstairs I catch a glimpse of somebody being hurriedly bustled out of the private office, and the great man himself comes to the door, smiling, and as I take his outstretched hand I am remembering other times that he has forgotten.

In the end—to make a long story short, as the saying is—Mr. Tuer, of 'Ye Leadenhall Press,' urged thereto by a mutual friend, read the book, and, I presume, found merit in it, for he offered to publish it if I would make him a free gift of the copyright. I thought the terms hard at the time (though in my eagerness to see my name upon the cover of a real book I quickly agreed to them), but with experience, I am inclined to admit that the bargain was a fair one. The English are not a book-buying people. Out of every hundred publications hardly more than one obtains a sale of over a thousand, and, in the case of an unknown writer, with no personal friends upon the Press, it is surprising how few copies sometimes can be sold.

I am happy to think that in this instance, however, nobody suffered. The book was, as the phrase goes, well received by the public, who were possibly attracted to it by its subject, a perennially popular one. Some of the papers praised it, others dismissed it as utter rubbish; and then, fifteen months later, on reviewing my next book, regretted that a young man who had written such a capital first book should have followed it up by so wretched a second.

8

From a photograph by Fradelle & Young.